A local man was kept off a recent flight because of a book he was carrying.

Everyone knows it is a bad idea to try and board a plane carrying a box cutter, a flight manual written in Arabic, or a sack full of mysterious white powder. But with ultra-tightened airport security, a book could also prevent you from boarding that plane.

No kidding. It happened just last week in Philadelphia.

Neil Godfrey arrived at Philadelphia International Airport around 9:30 a.m. on Wed., Oct. 10. His brother’s girlfriend dropped him off with plenty of time to spare before his 11:40 a.m. United Airlines flight. Godfrey was on his way to Phoenix, where his parents live. From there, the family was planning to head out for a vacation at Disneyland.

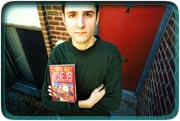

It is fair to say that Godfrey — brother of City Paper webmaster Ryan Godfrey — doesn’t look unusual for a 22-year-old kid living in Center City.

His outfit that day was typical: black Dockers, a T-shirt with a logo for the now-defunct Phoenix Gazette newspaper and New Balance running shoes. He has a medium build, recently dyed jet-black hair and a quiet demeanor.

When Godfrey stepped up to the ticket counter, the United clerk informed him he had been selected for a random baggage search.

“No problem,” he replied, going through the usual motions of checking his bag and getting a boarding pass. Now toting nothing but a novel and the most recent copy of The Nation magazine, Godfrey hiked through the concourse toward his boarding gate.

As he passed through the metal detector, an airport security guard furrowed his brow at Godfrey’s reading selections as they disappeared through the conveyor belt.

On the cover of the book, Hayduke Lives! by Edward Abbey, is an illustration of a man’s hand holding several sticks of dynamite. The 1991 novel is about a radical environmentalist, George Washington Hayduke III, who blows up bridges, burns tractors and sabotages other projects he believes are destroying the beautiful Southwest landscape.

“For the first time, it occurred to me the book may be a problem,” Godfrey recalls.

He proceeded through the security checkpoint and sat down to read near his boarding gate. About 10 minutes had passed when a National Guardsman approached Godfrey.

“He told me to step aside,” Godfrey says. “Then he took my book and asked me why I was reading it.”

Within minutes, Godfrey says, Philadelphia Police officers, Pennsylvania State Troopers and airport security officials joined the National Guardsman. About 10 to 12 people examined the novel for 45 minutes, scratching out notes the entire time. They also questioned Godfrey about the purpose of his trip to Phoenix.

The fact that Godfrey recently dropped out of Temple University and has yet to find a job may have piqued suspicion of law enforcement officials even more.

“The fact that I don’t work or go to school may have contributed to them thinking I have nothing to live for,” Godfrey speculates.

Eventually, one of the law enforcement officials told Godfrey his book was “innocuous” and he would be allowed to board the plane.

“I was pretty shaken up,” he says. “But I also felt guilty that I hadn’t realized bringing this book to the airport may cause a problem.”

Another 10 minutes or so passed while he sat in the waiting area. A female United employee — Godfrey failed to jot down her name — came over and informed him that he wouldn’t be allowed to fly, “for three reasons.”

The first reason, she said, was that Godfrey was reading a book with an illustration of a bomb on the cover. Secondly, she said, he purchased his ticket on Sept. 11. (Godfrey bought the ticket on Priceline.com shortly after midnight, at least eight hours before the World Trade Center was attacked).

And the final reason cited by the United employee was that Godfrey’s Arizona driver’s license had expired. The employee pointed to a date to substantiate this allegation.

“No,” Godfrey told her. “That’s the day the license was issued.”

The woman then pointed to another date on the card, Feb. 17, 2000, contending it was the expiration date. Godfrey countered that the date identified him as “under 21” until then.

“Too bad, it’s too late,” the flight attendant informed him.

A defeated and disappointed Godfrey reclaimed his luggage and was escorted out of the airport.

When he got home, Godfrey did what a lot of guys do when they need consoling — he phoned his mom.

Godfrey’s mother offered to call United and attempt to straighten things out. A central reservation clerk assured her that her son was not banned from ever flying United again. She booked him on a different flight to Phoenix, this one departing Philadelphia at 3:04 p.m. that same afternoon.

Godfrey scurried back to the airport, leaving the Abbey novel at home. He exchanged it for a seemingly benign novel, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban.

When Godfrey arrived at the airport around 1:15 p.m., his luggage was again searched. But as Godfrey passed through the metal detector, a police officer recognized him from the commotion just a few hours earlier. The cop pulled Godfrey aside and made a few phone calls. Ultimately, he declared that everything checked out fine. But a National Guardsman standing nearby vetoed that decision.

“This time, they took my Harry Potter book and about four people studied it for 20 minutes,” Godfrey says.

Finally, at about 1:45 p.m., officials apparently felt reassured that Godfrey was not a security threat. They told Godfrey he would be permitted on the plane, but that he couldn’t pass through security until 2:30 p.m.

At the appointed time, an escort took Godfrey through security, while at least 15 law enforcement officials looked on. Rather than taking Godfrey directly to his gate, however, he was ushered into a private interrogation room.

“They patted me down and found nothing,” Godfrey says. But when he emerged from this room, Burt Zastera, supervisor of airport operations for United, told him he would not be allowed to fly.

“He told me he didn’t know the reason why, that he was ‘just conveying the information,’” Godfrey recalls. Zastera gave Godfrey a contact number he could call for a full explanation.

Godfrey’s father called that number and was told his son was banned from flying United because he cracked “a joke about bombs.”

“That is totally false,” Godfrey says, pointing out that no one at the airport ever mentioned this to him. Plus, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations stipulate that any passenger who jokes about explosives be arrested on the spot. By contrast, Godfrey was never charged or even accused of breaking the law. In fact, Philadelphia Police officers didn’t even file an incident report, according to department spokesman Cpl. Jim Pauley.

Other airport and law enforcement officials have very little to say about Godfrey’s treatment.

Zastera says he is “not allowed to comment” on what happened because it is a security matter. United Airlines spokesman Chris Bradwig says he is “unaware” of the Oct. 10 incident.

“Even so, we don’t comment on security matters,” he says.

A supervisor with Aviation Safeguard, the company United contracts to man security checkpoints in Philadelphia, denied responsibility for detaining Godfrey.

“The only ones who determine who can’t get on a flight is the airline,” says an Aviation Safeguard supervisor, who refused to provide her name. “We don’t stop any books.”

Philadelphia International spokesman Mark Pesce agrees that only individual airlines determine whether to permit a passenger to fly.

“When a passenger passes through security, it is under the jurisdiction of the airline. We don’t get involved,” he says, adding that stories like Godfrey’s are likely to become increasingly common.

The FAA has no policy regulating “specific types of reading material,” says spokeswoman Arlene Salac.